Medieval mystery plays

Medieval mystery plays in Lincoln

A summary by T.L.J. Holt

Although in the twenty-first century the term ‘mystery’ is often associated with the crime and mystery genre, fifteenth and sixteenth century mystery plays were a genre of community plays that were loosely based on bible stories.

Through them, we can gain a glimpse into popular culture from the late medieval and early modern periods, as they reflect the attitudes and beliefs of the people that created and performed them for local audiences.

They contain plays both humorous and sombre, with tales of biblical figures and events that did not always feature in the bible itself.

Despite their modern obscurity, remnants and references to their existence have echoed across the centuries and they influenced several later works including Shakespeare’s 'Macbeth'. His infamous porter scene harks back to the imagery used in earlier mystery plays that featured the Harrowing of Hell, where Christ descended to release souls imprisoned there.

Multiple cities are known to have had mystery play cycles associated with them, and several documents reference the existence of similar cycles that were performed in Lincoln. It is clear that they played a large role in medieval Lincoln and were performed here for hundreds of years.

During the late medieval period, Lincoln was a thriving city of great renown, and her diocese stretched from the River Humber to the River Thames. It was the largest in England and was composed of eight archdeaconries: Bedford, Buckingham, Huntingdon, Leicester, Lincoln, Northampton, Oxford, and Stow.

Though play fragments survive from the archdeaconry of Northampton, little is known to survive from Lincoln itself. Several attempts have been made to find and locate Lincoln’s plays and, during the twentieth century, the hunt for them led scholars to the

N-Town manuscript.

Created between 1450 and 1525, the N-Town manuscript contained 42 separate plays, beginning with The Creation of Heaven and ending with Judgement Day.

Recent scholarship has revealed that this manuscript was likely to have originated in the neighbouring region of East Anglia but, for a short time, they were referred to as the Lincoln Mystery Play Cycle.

Today, we know this cycle as the N-Town plays, a name that comes directly from the manuscript itself:

"A Sunday next, if that we may

At VI of the bell we gynne oure play

In N. town; wherefore we pray

That God be youre spede."

It is believed that the 'N' here stands for 'nomen', meaning 'name', which was a common abbreviation in medieval documents.

Scholars today think that these plays were staged by a travelling troupe of players who simply substituted the name of the town they were performing in. This contrasts with several other surviving sets of mystery plays, such as those of Chester, Coventry and York, which were originally performed by craft and trading guilds on wagons during the Corpus Christi Festival in their respective cities. Indeed, it is likely that Lincoln's plays resembled the cycles of Chester, Coventry and York in this regard.

Maintaining the tradition of the original performers of the N-Town Plays who strove to bring them to different audiences across the East of England, the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust are honoured to perform them in a range of local venues across Lincolnshire today.

More about the N-Town medieval mystery plays

A summary by Ruth Hewitt

Human nature doesn't change

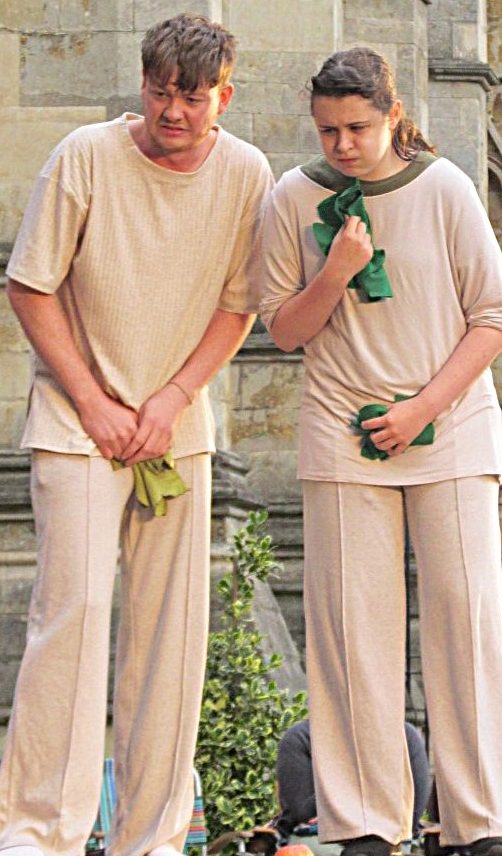

When watching the mystery plays in performance, what’s striking is how fundamental human nature has, seemingly, remained unchanged from the medieval era to today. There is a universality to the topics of the plays: a mother’s grief at seeing her son killed; the ongoing fight between good and evil; the difficult choices that must be made and subsequently paid for; the hardship of ordinary people in difficult times; the arguments and tenderness of typical human relationships; the sacrifices made by people for each other. The whole range of human emotions are contained in these plays.

The battle between good and evil

Lucifer is portrayed as a rebel upstart seeking to gain control of the world and challenge God’s authority over it, but we see his power ebb and flow in line with the support he gains from mortals. The parallels with modern politics, beliefs and the universality of human relationships and their dynamics are truly striking.

The mystery plays will have you laughing, fearful and moved to tears by the situations and characters. There is the impish behaviour of Lucifer’s crew as well as the carping and two-faced characters, such as Raise-Slander and Backbiter, who we find in stories throughout the cycle coming in at key points to cast doubt, suspicion and stir up trouble.

There are also serious dilemmas such as that faced by Judas deciding to reveal Jesus’ whereabouts to the Priests after he has lost faith in the mission.

A real spectacle

You will be mesmerised by the spectacle of some key scenes in the N-Town Plays. For example, Noah’s family braving the storm whilst other people around them drown.

There is also so much fun in the mystery plays. Though they are loosely based on well-known bible stories, they often take a comedic approach while adding a local flavour, in a similar way to pantomimes - for example, there are built in jokes to poke fun at neighbouring towns.

With music, songs and dance, not to mention amazing costumes and staging, the Lincoln Mystery Plays make use of physical theatre, symbolism and, sometimes, puppetry to create strong representations and atmospheres in which the stories can be dramatically revealed.

Many of the scenes are genuinely spectacular.

Contemporary relevance

Albeit that church-going in general and knowledge about Christian religious stories have massively reduced since the time these plays were first performed, the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust believe that, in reviving this ancient art-form, we are able to give them a contemporary relevance and resonance.

When our 2022 set of plays were reviewed by Heather Mitchell-Buck, an academic researcher, she described them as a "lovely little miracle", noting that the over-riding message of these "little-known gems from the past" was to “be kind".

"Whether or not an individual audience member believes in heaven or hell, each of us is able to heed the call to be good neighbours”. This was especially important at a time when we were coming out of our covid isolation and appreciating the value of local communities to our wellbeing and survival. As Heather put it, “mystery plays are not just community theatre; rather, they are theatre that teaches us how to live in a community”.

Don't just take our word for it; come along to a performance and see for yourself!

History of the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust

Reminiscences of Keith Ramsay who, with others, set up the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust in 1978 and was its director for the first 22 years are given below. These comments were printed in the programme for the 2000 performance, after which Keith retired from the LMPT.

We will be forever grateful for his massive contribution to the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust.

Standing in the Nave of Lincoln Cathedral after my 1976 production of the seventeenth century Oberufer Plays, a Bishop Grosseteste College production, the then Chancellor of the Cathedral came up to me and simply said: “Why don’t you do our plays, Keith?” That was the start of twenty-two years of directing the Lincoln Mystery Plays. At that time, it was widely thought that the N-Town text was, in fact, Lincoln’s missing cycle of Mystery Plays. We know now that N-Town is an East Midlands touring text from the fifteenth century. We have, however, given N-Town a home in Lincoln, as John Harris writes in his book “Medieval Plays at Lincoln”.

I don’t claim to have staged the first twentieth century production of these plays. There was Margaret Birkett’s pioneering production in Grantham in 1967 and Clare Veneables Theatre Royal production in the Cathedral in 1970, but I believe I now have the doubtful distinction of having directed more full-scale productions of the of the Mystery Plays than anyone else. My wife describes me as obsessed. I suppose I am.

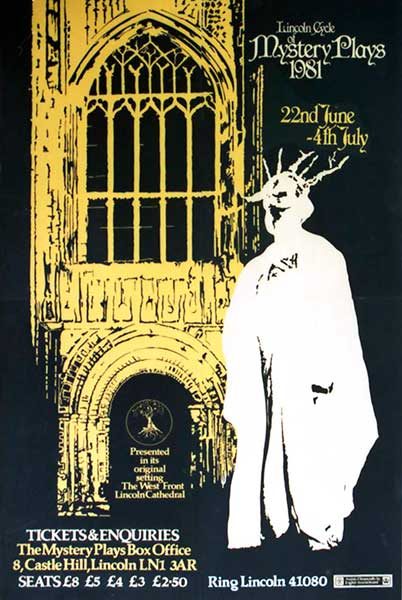

My first major production was in 1978. I had managed to persuade Rex Davis, our Sub-Dean, to Chair our planning committee. His dynamism fuelled the two first productions (1978 and 1981). Without him there would have been no Mystery Plays in Lincoln. The Company owe him much. The 1978 production was set under Lincoln Cathedral's central tower. This is a very dramatic spot, visually overwhelming but, alas, the spoken work goes straight up the tower. So, much of the dialogue was missed. However, the production played to good houses for a fortnight and was generally thought a success.

Fired by this success, I tentatively proposed that the 1981 production should be in the original medieval setting, namely, outside the West Front. To my surprise and joy, Rex thought this an excellent idea. We had the road blocked off and a thousand seater rake erected. The show hit one of the coldest ends to June on record. We only had a fullish house on the last two nights. The weather had improved. This was possibly my most ambitious production prior to this, 2000, one. The acting area was too big. The early plays especially lacked the intimacy so required of medieval drama. However, as in 1978, we had the late Nigel Clarke as our lighting designer. Nigel was a genius with light. If he had lived beyond his thirties, he would have been one of Britains’ leading lighting designers. Nigel’s lighting made my production look much better than it, in fact, was. His lighting of the Crucifixion, Resurrection sequence was exquisite. I understand the late Bishop Riches would pass by each night to see this section of the plays.

The photographs the young Gus de Cozer took of the concluding plays in 1981 were the reason that the show started on a series of continental tours. I took the slides to Leuven University to an international conference on medieval drama. Armed with Gus’s slides, I managed to impress enough academics to be given an invitation to take a small-scale production to the 3rd International Colloquium on Medieval Drama where we were a sort of up-market cabaret – a suitable end to a day of erudite lectures.

The Colloquium was held in Viterbo, a medieval town in central Italy. Fifteen lecturers and students from Bishop Grosseteste College set out in two mini buses for Italy. We stopped a few days in Neustadt, Lincoln’s twin town in Germany, and performed in the courtyard of the Rathaus. Our arrival in Viterbo was low key. Our hotel seemed to be doubling as a bordello. God (Jack Jones) advised the girls to lock their bedroom doors and not to sit on the lavatory seats. The night of the performance the heavens opened at 6.00pm Our production was alfresco. However, by 9.30 the skies were a dark blue, swallows were cutting across the courtyard. God stood high above the audience at the top of a medieval stairway. The sound of John Bannister’s small group of girls singing the Sanctus echoed up into the Italian night. Two tears glinted from under God’s gold mask. I thought that this would be a night to remember. And so it turned out to be. The next day, we felt like pop stars. I have not been hugged by so many Italian ladies since.

The outcome of this production was an invitation to take the production to Rome for Easter 1984, to an international festival of sacred drama. It was held in Holy Week in Holy Year and was a first. Drama had not previously been sanctioned by the Pope during Holy Week. Three young ladies watching the Crucifixion scene on Good Friday were not weeping silently, as an audience sometimes does in England, they were howling in distress. We took this as a compliment.

So, it was back to Lincoln for the 1985 production in the Cloister of the Cathedral. This was altogether a happy production under the benign chairmanship of Derek Hawker, then Principal of the School of Art. One performance nearly ended in disaster, however. The torches used at the Crucifixion set off all the Cathedral fire alarms during the deposition scene. The fire brigade arrived in force. The poor actor playing Jesus was left hanging on the cross, forgotten. Dean Fiennes turned off the alarms; John Bannister started singing the Agnus Dei with his choir. We raised the cross. Such is the power of that music that following such chaos; the audience were straightway back into the drama. The Chairman took me back to his house in Vicar’s Court after the performance and gave me a very stiff whiskey.

We had one more foray to an academic conference, namely, Perpignan University, where we played in the Cathedral (1986). If the acoustics are difficult in Lincoln Cathedral, Perpignan’s black marble pillared nave is almost impossible. We all had to face front and speak very slowly. Apart from actors with sunstroke, we had a joyous time.

In 1989, we were invited by Paul Parker to take the production to America. We played in Southwell for a week and in Lincoln for a fortnight. The twenty-three for the American tour had to be chosen. We had five professional actors, including Colin MacFarlane (The Fast Show) and my sister Louie (Dora Wexford in the Ruth Rendell Mysteries). This was a triumphal tour. We played to audiences of up to 7,000 per night, and they stood up to applaud at the end.

1993 saw a small-scale production in the Cloister and a large-scale follow-up in the Nave in 1994. We had the addition of a large contingent from the Lincoln Shakespeare Company. Many of these young people had been drama students at Bishop Grosseteste College, and their youthful vigour gave the production a useful shot in the arm. Many of these not quite so young people remained members of the Company for the next twenty years.

In 1997, we staged the last full-scale production of the plays in the Cloister. In some ways, though not a financial success, the company felt we produced a very satisfying end result. It was far too long – something I have avoided in 2000.

The production of 2000 uses much of the Cathedral – all areas we have used before but not all in one production. The acquiring of a £30,000 Millennium Grant by our administrator, Helen Mason, has made it possible to spread our wings a bit this time. The scale presents a challenge to our lighting designer Dave Dray, a challenge he can well meet. Our musicians, led by Richard Still, have produced a CD of the music. We look forward to the week in Southwell again and the exciting prospect of the Lincoln venue. Then there are plans to tour to Europe next year, to Trondheim and Camerino (which we first played in 1998).

I have been so fortunate to have such a fine band of friends to work with, and I have been privileged to have this magnificent building to use for my productions. There is no doubt but that the majestic soaring heights of this great Cathedral are the Company’s secret weapon. Take away the Cathedral and the production loses a major dimension. I have indeed been a most fortunate man.

In memory of Bob Shirley - Lincoln Mystery Plays performer and Board Member for many years

Obituaries from those who knew him -

Michael Church and Mary Scott

Bob Shirley was one of the founding members of the Mystery Plays Company back in 1978 when it was still very much a project associated with Bishop Grosseteste College (as it was then called) and, inspirational Senior Lecturer in Drama there, Keith Ramsay. Bob Shirley also worked at BGC as a senior lecturer in English as well as contributing to Education and Professional Studies.

Bob played a variety of parts in the first full production but, later, it was the part of Joseph that he was to make his own. He suited the part perfectly with his down-to-earth appearance and voice, combining Joseph's irritation and bafflement at his situation with his deep affection and care for Mary and the babe. In many productions, 'real babies' often featured and Bob proved remarkably adept at calming them, when needed.

Later, Bob became treasurer of the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust Board, a role which he carried out with his customary thoroughness and attention to detail. However, he remained immune to the joys of the Excel spreadsheet and successive Chairs poured over the many pages of annual accounts presented in his distinctive handwriting.

When, in 2000, Keith finally retired from the LMPT and from directing the plays with such love and inspiration, many of the 'regulars' retired with him. However, Bob continued to devote himself to the Trust, supporting and advising new trustees and performers and continuing to perform himself; he was a notable Noah in the 2004 production.

Bob also performed in several of the interim productions including the stunning 'The Last Post' in 2014 and, again playing Joseph, in 'The Journey' - a promenade nativity performed annually around Lincoln Castle for many years which became a much-loved feature of the City's Christmas celebrations. Bob, as Joseph, moved from scene to scene through the Castle grounds with Mary and his faithful friend Copperfield the donkey - though it was never quite clear whether Bob was leading the donkey or the donkey was leading him. Finally, Bob had to give up performing due to ill health.

Bob Shirley was a fine actor, combining a keen intelligence with a down-to-earth, sympathetic style which connected with audiences and fellow actors alike. To play alongside him was a delight. Bob also made a major contribution to the Lincoln Mystery Plays Trust for over thirty years. He will be much missed.

Michael Church

Mary Scott knew Bob through his acting and directing in a variety of Theatre Companies in Lincoln, including The Phoenix Players, as well as the Lincoln Mystery Plays

Bob Shirley was a lovely and very knowledgeable man. We acted together for many years often as stage husband and wife, such as in 'Time of my Life' by Alan Ayckbourn. My personal favourite Ayckbourn role that Bob played was Reg in 'The Norman Conquests' - he was hilarious!

He directed Michael Church and I in Harold Pinter's 'The Birthday Party' and imparted a wealth of useful information about both Pinter and the play.

During 'The Journey', Ally Perkins' brainchild, for which all profits went to The Kidney Patient Association, Bob formed a strong friendship with the donkey, peppermints in his pocket sealing the deal!

His last role with The Phoenix Players was Knox in 'Breaking the Code', playing the part to the same high standard everyone had come to expect.

He is sadly missed and our thoughts are with his wife, Pat.

Mary Scott

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.